Unseen and Unsettling

FOTÓMETRO’S PHOTOGRAPHIC DISRUPTIONS IN PROOF OF EXISTENCE

Published on May 8th 2025 as part of UNHiNGED #5 - Flesh and Form.

For Rona Bar and Ofek Avshalom, photography is more than just a visual medium—it is a means of reinterpreting the world through narrative and aesthetic experimentation. Their photographic duo, Fotómetro, is known for blending reality and fantasy, crafting surreal imagery that interrogates identity, individuality, and human form. Their latest project, Proof of Existence, pushes these themes even further, presenting characters that challenge notions of normality and redefine what it means to be seen.

I first met Ofek and Rona while they were working on their project Us, an intimate exploration of relationships and overlooked love stories. For over two years, they photographed couples in their homes across Israel, the UK, and Europe, bringing visibility to relationships often ignored by mainstream media. That project focused on intimacy and human connection. In contrast, Proof of Existence amplifies the bizarre, creating exaggerated yet deeply personal portraits that invite viewers to reconsider identity and form. Like the staged, dreamlike tableaus of Cindy Sherman or the eerie, hyper-stylized portraiture of Gregory Crewdson, Fotómetro’s work distorts perception, constructing characters that exist in the liminal space between documentation and fiction.

Although I wasn’t able to meet with Rona for this interview, Fotómetro is an inseparable creative entity. As Ofek and I spoke, it became clear that Proof of Existence is not just a study of those in front of the lens but also of those behind it. The project is a collaborative effort, involving designers, stylists, and models who all contribute their unique perspectives to the final images.

At its core, Proof of Existence seeks to normalize the weirdness within us all. The project features strikingly designed characters, each set against seemingly ordinary backgrounds, forcing the viewer to question what is truly “normal.”

“We didn’t want to just ‘represent’ people,” says Ofek. “It wasn’t about documentation, but about pushing perception further, making the familiar unfamiliar.”

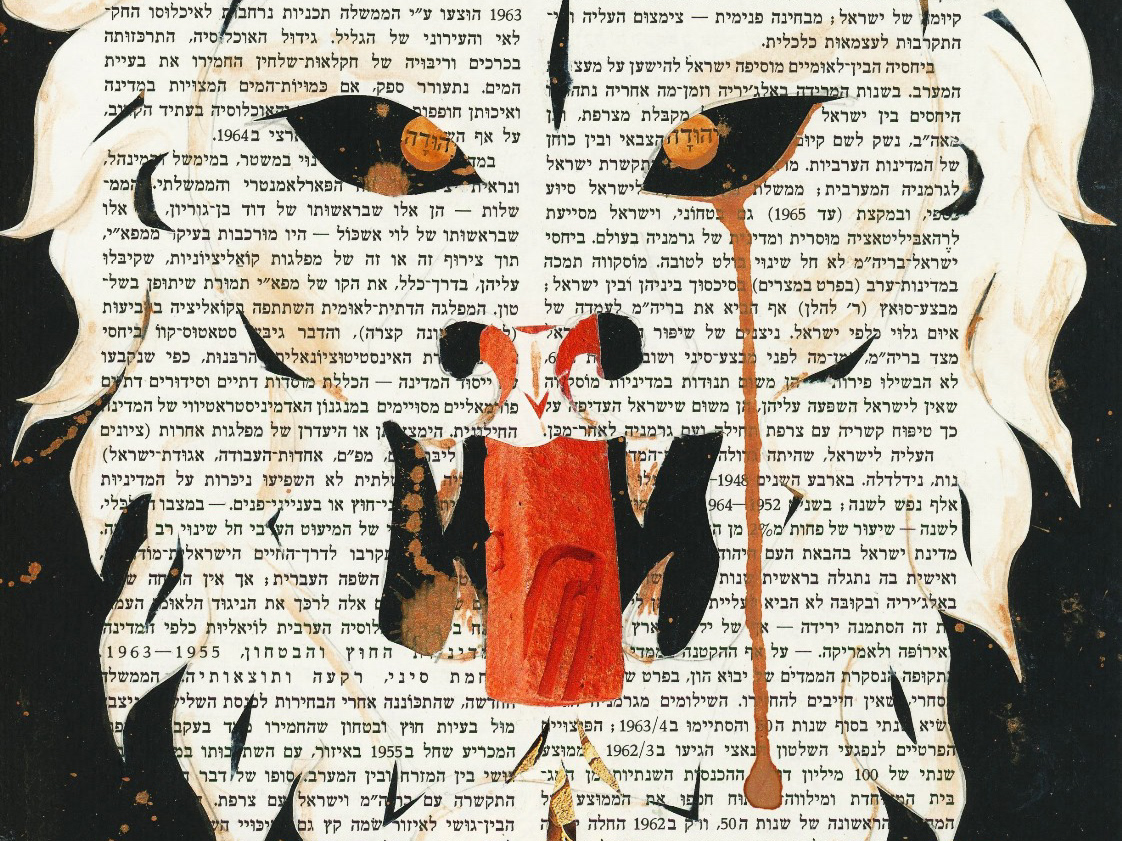

Among the project’s many arresting images are those of Lois and Carey Marvin, a Jewish mother and daughter, photographed before Shabbat dinner. Their image reflects themes of tradition and generational connection, but also complicates them within the project’s surreal aesthetic. Another powerful image features Diogo, dressed as his drag persona, Co Kendrah, captured with a pig nose, embodying transformation and theatricality. Gianna T, an artist, is portrayed in his studio, reinforcing the theme of self-creation.

These images straddle documentary and staged photography, forcing viewers to ask: Where does reality end and fiction begin?

“It’s about perception of the body,” Ofek explains. “Sometimes the body itself is the focus, but sometimes it’s the way an outfit engulfs someone or the way an object interacts with them. It’s about how identity is expressed through form.”

A crucial aspect of Proof of Existence is the discomfort it evokes. Ofek wants his viewers to feel unsettled, to experience a moment of dissonance before questioning why they feel that way.

Discomfort has long been a powerful tool in art and photography, forcing audiences to confront their own assumptions, biases, and limitations. In the 20th century, photographers like Diane Arbus captured subjects on the fringes of society, using intimacy and unease to challenge conventional beauty and normalcy. While Joel-Peter Witkin’s grotesque yet carefully composed images provoked visceral reactions, questioning societal taboos around the body. More recently, contemporary artists such as Zanele Muholi use discomfort to highlight marginalized identities, urging viewers to reconsider their gaze and positionality.

Fotómetro follows in this tradition, using theatrical styling, surreal compositions, and exaggerated personas to destabilize perception. Proof of Existence does not seek to simply unsettle—it invites introspection, asking viewers to question why certain bodies, expressions, or aesthetics evoke unease in the first place. By leaning into distortion and theatricality, Fotómetro amplifies the liminal, ensuring that what at first feels unfamiliar ultimately becomes undeniable.“Discomfort is a powerful tool,” he explains. “It forces you to confront something within yourself. If an image makes you uneasy, ask yourself—why? What is it about this subject, this body, this setting that feels strange to you? More often than not, it reveals ingrained perceptions and biases that we don’t even realize we carry.” By prompting these moments of self-reflection, Fotómetro challenges viewers to reconsider their assumptions about identity and representation.

This deliberate unease is heightened by Fotómetro’s careful manipulation of styling and form. Makeup and costume are not just aesthetic tools in Proof of Existence—they function as distortions of identity, altering how the body is perceived and challenging the viewer’s assumptions about self-presentation. Fotómetro worked closely with makeup artist Elle McMahon and stylist Bessy Huang, collaborating with emerging designers to create characters that feel otherworldly yet grounded.

“We wanted to step beyond traditional portraiture,” says Ofek. “Makeup and costume aren’t just aesthetic choices here—they’re extensions of the body, ways of reshaping how identity is perceived.”

The project also challenges conventional beauty norms through its collaboration with Zebedee Talent Agency, which represents individuals with disabilities and visible differences. For Fotómetro, inclusion wasn’t about representation for the sake of it, but about fundamentally shifting the lens through which such individuals are portrayed.

“We didn’t want to fall into the trap of ‘inspirational’ photography,” says Ofek. “Too often, people with disabilities are framed in narratives of strength or struggle. We wanted them to simply exist in this world we created—without explanation or justification.”

This ethos runs throughout the project, which celebrates differences not as anomalies but as intrinsic to the human experience. Proof of Existence forces us to question why certain bodies and identities are considered unusual in the first place.

While Proof of Existence was conceptualized in Tel Aviv, the project only fully took shape after Ofek and Rona relocated to London. The move provided more than just a logistical advantage—it reshaped their entire approach.

London’s diverse artistic network allowed Fotómetro to collaborate with designers, stylists, and performers who deeply resonated with the project’s themes. “We weren’t just casting people—we were building a creative community around the project,” Ofek notes.

Their integration into London’s scene also led to a more collaborative approach. While their earlier works were largely controlled by the duo alone, Proof of Existence embraced a larger team, allowing space for other voices to shape the final aesthetic.

“It was freeing,” says Ofek. “Instead of us dictating everything, we let the process take on a life of its own.”As a creative duo, Fotómetro is more than just a name—it is an artistic philosophy. Derived from the Italian word for a light meter (fotometro), the name reflects their emphasis on light, perception, and storytelling.

“We came up with it when we started working together,” says Ofek. “It was a way to create an identity outside of just ‘Ofek and Rona.’ It made us feel more like a collective than two individuals.”

While Ofek handles lighting and Rona focuses on post-production, their decision-making is entirely shared. “We don’t finalize anything unless we both agree,” Ofek states. “Our creative process is a constant dialogue.”

As Fotómetro moves forward, their work continues to evolve. Proof of Existence is being developed into a photobook, a tangible manifestation of its themes.

“The book itself is proof of existence,” says Ofek. “It’s an object, something real. That’s important to us.”

Beyond that, the duo has already begun work on a new project that examines Jewish identity through an unconventional lens.“There’s this idea that Jewish identity is always represented in very specific ways,” says Ofek. “We want to challenge that, to visually explore it in ways that feel unexpected—even uncomfortable.”

As our conversation ends, one thing is clear: Fotómetro isn’t just capturing people; they are reshaping the way we perceive them. Their work doesn’t settle for representation—it warps, expands, and reinvents it, forcing us to confront the fluidity of identity, the instability of form, and the limits of our own gaze.

Proof of Existence challenges the notion that bodies and identities are fixed. Instead, it reveals them as constantly shifting, molded by perception, space, and the context in which they are placed. It embraces the grotesque, the exaggerated, and the surreal as a way of breaking apart what we assume to be natural or familiar. The discomfort it provokes is not incidental—it is a deliberate invitation to question why certain bodies or forms feel unfamiliar in the first place.

Whether through Proof of Existence or their next project, Fotómetro continues to disrupt the frameworks through which we understand identity and selfhood. Their images linger, distorting and evolving in the mind long after they are seen—a reminder that existence is never static, and neither is the way we choose to see it.

Fotómetro is currently based in London and is represented by Cicek Gallery (@cicekartgallery). To see more of their work or get in touch, you can find them on Instagram: @ronabarphotos, @ofekavshalom, and @fotometro.art.